|

Table of Content - Volume 13 Issue 1 - January 2020

Dysgerminoma with pregnancy and viable baby: A case report

Kharane Priyanka1, Tondage Ganesh2*, Munde Shivkanta3

1IIIrd Year Junior Resident, 2Associate Professor, 3Assistant Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, S.R.T.R.G.M.C., Ambajogai, Beed, Maharashtra, INDIA. Email: kharane.priyanka@gmail.com

Abstract Dysgerminomas are the most common of primitive germ cell tumors of the ovary, accounting for 1-5% of all ovarian malignancies. The reproductive age group females are most commonly affected, thereby causing problems in conception and if pregnancy occurs, it leads to feto-maternal compromise. It is extremely rare to have a successful natural pregnancy, with viable child birth with a coexisting dysgerminoma, without any assisted reproductive interventions. We hereby report a case of successful spontaneous natural pregnancy in a G3P2L1D1, associated with dysgerminoma, with no feto-maternal compromise.

INTRODUCTION Dysgerminomas are germ cell tumors of ovaries with excellent prognosis after surgery and/or chemotherapy. The challenge, however, lies in the fact that dysgerminomas, unlike other tumors of the ovary affect females in the reproductive age group, thus preservation of fertility even after treatment is uncertain; and if a concurrent pregnancy has occurred, then should it be allowed to progress? We present a case where the patient had no any prior intervention for the diagnosis and presented to us only when she had abdominal discomfort due to increased abdominal girth.

CASE REPORT A 22 years old female G3P2L1D1 with 8 months of amenorrhea referred from PHC, Sonpeth to our institute i/v/o large ovarian mass with abdominal fullness and decreased appetite since 15 days with difficulty in defecation since 4-5 days. Without any history of prior ANC check-up. There was no history of any menstrual irregularity or any contraceptive intake in the patient before the pregnancy. There was history of previous FTND 3 years back and history of 6 months IUD. Also there was no history of any major medical or surgical illness in the past or family history of any gynaecological and breast malignancy. No history of any chemotherapeutic drugs intake taken. Ultrasonographic examination revealed a pregnancy of 33wks 4days with e/o capsulated, mixed echogenic solid mass with no papillae or septi, of size 18.4cm * 12.2cm arising from left ovary suggestive of? ovarian teratoma with right sided adnexal structure showing no pathology. On examination patient was afebrile, pallor ++, PR-94/min, BP- 110/74mmHg.on per abdominal examination overdistended abdomen with cephalic presentation with presenting part felt above the mass. FHS was heard regular 140/min with uterus relaxed. On per speculum examination cervical os not seen. On per vaginal examination cervical os could not be reached, posterior fornix is full of mass, POD was tense and tender. On per rectal examination is rectum no other mass felt with rectum loaded with fecal matter. Patient was given enema and stool passed. In view of a viable foetus, emergency surgery was planned immediately after coverage of steroids due to severe pain in lower abdomen not related to uterine contraction. Laparotomy with Lower segment Caesarean Section was carried out. An enlarged left ovary with bosselated outer surface and intact capsule was noted. Ovarian mass of solid, fragile tissue, arising from left ovary and occupying the whole pelvic cavity behind the uterus was present. No abnormality was observed in any other intra-abdominal organ and Right adnexal structures. A per-operative diagnosis of pregnancy with concurrent ovarian tumor was made. Left salpingo-ovariotomy was performed and a live male baby, appropriate for gestational age was delivered. The patient was referred to cancer institute for chemotherapy due to unavailability of the same in our institute.

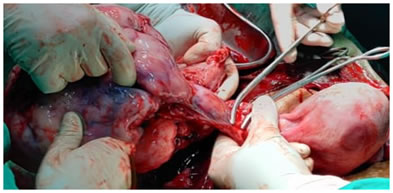

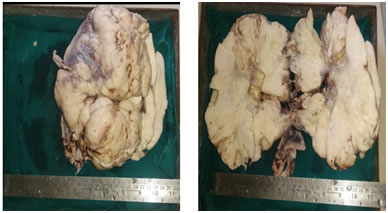

Intraoperative picture showing left ovarian dysgerminoma PATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS GROSS: Received specimen in 4 pieces of ovary – first of size 19*17*8 cm , second of size 17*9*6 cm, third of size 7*6*3 cm and fourth of size 5*2.5*2.5 cm. External surface – capsulated, bosselated, congested blood vessels. On cut section – solid firm homogenous whitish coloured mass along with foci of hemorrhage and necrosis.

Grossly cut section shows solid, firm, homogenous, tan colored growth with foci of hemorrhage and necrosis

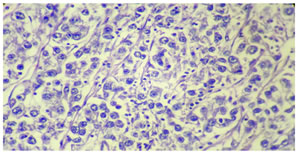

MICROSCOPIC EXAMINATION: Multiple sections studied revealed partly encapsulated tumor mass composed of well defined nest and cords of tumor cells separated by thin fibrous septa infiltrated by lymphocytes. Individual tumor cells are of uniform size having large nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Cells are having abundant finely granular to clear cytoplasm. Occasional multinucleated giant cells are also evident. Microscopically, the fallopian tube was normal. A final histopathological diagnosis of ovarian dysgerminoma (left side) was made.

Tissue section shows well defined nests of large uniform tumor cells with granular nuclear chromatin, prominent nucleoli and finely granular cytoplasm seperated by fibrous strands containing lymphocyets, Hematoxylin and Eosin * 40

DISCUSSION Ovarian tumors are broadly classified into three types based on their origin, epithelial, sex cord and germ cell tumors. While epithelial variety largely predominate, germ cell tumors (GCTs) are rare, comprising about 30% of all ovarian neoplasms and 3 % of all ovarian malignancies.1 Ovarian Germ cell tumors, derived from the primordial germ cells, are further divided into subgroups based on the histological features. Mature teratoma being the commonest benign variety while dysgerminoma are the commonest malignant germ cell tumor.2 Among the non-dysgerminoma group are yolk sac tumors, endodermal tumors, immature teratoma, embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma and mixed germ cell tumors. The major challenge with dysgerminoma, the commonest malignant variety of germ cell tumor, is that they predominantly affect young women. About 75 % of dysgerminoma occur between the ages of 10 and 30 years and thus can affect the fertility or may be associated with pregnancy.1 Lee et al reported the mean age of women in their study as 23.8 years (Range 4-63 years).3 Several cases of pregnancies after treatment of dysgerminomas with various modalities including surgery and chemotherapy, have been reported previously.4,5 Gershenson has reported that natural conception is possible in case of germ cell tumors of the ovary, a finding similar to our case.6 Hirota et al. in their study reported the frequency of ovarian tumor associated with pregnancy ranges from 1:80 to 1:2200 deliveries.7 But natural course of pregnancy in cases of dysgerminoma is extremely difficult, due to large sizes of the tumors, irregular menstruation, and collection of fluid as well as tubal adhesions. Ovarian tumors generally remain asymptomatic, until they are discovered due to their large size or related complications.8 In the current case, dysgerminoma was diagnosed due to disproportionate enlargement of the abdomen because of large ovarian mass with pregnancy. The patient in this report deserves attention as she conceived naturally, without any assisted reproductive technique and spontaneous delivery was possible with a coexisting dysgerminoma. Quirk and Natarajan have reported that approximately 75% of women with a dysgerminoma present with clinical stage Ia disease.9 Dysgerminoma disease staged Ia (ie, confined within the capsule of only one ovary) is best treated with simple unilateral salpingo-ovariotomy and residual microscopic disease is extinguished readily with chemotherapy, to which these cells are highly responsive.10 The best outcome for both mother and child depends on early diagnosis and excision of the ovarian lesion while it is still intact. The pathologic type and extent of ovarian carcinoma seem to be the most important determining factors in the maternal prognosis. Several authors have stated that once the existence of ovarian malignancy is suspected, immediate laparotomy is indicated regardless of the stage of gestation.11-13 But Jubb, supports a more conservative approach in younger pregnant patients, especially if the ovarian lesion is intact or is of the pseudomucinous type.14 There still remain unsolved problems concerning conservative management before and after termination for early-stage ovarian malignancy associated with pregnancy. When we encounter FIGO stage-Ib or higher ovarian malignancies in the second trimester and the patient strongly wishes to continue with the pregnancy, very serious problems arise as to whether conservative surgery and chemotherapy should be performed in the gravid woman or not. Antineoplastic agents can be mutagenic or teratogenic, or cause fetal growth retardation or fetal death when used in the first trimester.15 However, Kim and Park, have documented the use of chemotherapeutic agents during the second trimester and delivery of a normal infant.16 Patterson et al. in their review of the close surveillance policy for stage I female germ cell tumors of the ovary, stated that five-year survival rate for Stage Ia dysgerminomas is over 95%.17 Our patient was advised close follow up in terms of regular pelvic examination and abdominal CT scan as there was no evidence of metastasis and complete resection of tumor mass was possible in our case.

CONCLUSION The long-term outcome of patients with pure ovarian dysgerminoma is excellent. Patients can be treated with fertility-sparing surgery and can expect good reproductive outcomes. A dysgerminoma confined to a single ovary, with ascites, although large may not metastasize or seed the peritoneal cavity/fluid or other pelvic/abdominal organs and a natural course of pregnancy with viable child birth may still be possible.

REFERENCES

Policy for Articles with Open Access

|

|

Home

Home