|

Table of Content - Volume 18 Issue 1 - April 2021

Expanded dengue syndrome in pregnant and non-pregnant females

Santhi P John1, Suresh I2*, M Swamy3

1Post graduate Resident,2Associate Professor, 3Professor and HOD, Department of General Medicine, Kamineni Academy of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, L B Nagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, 500068, INDIA. Email: drsuresh8287@gmail.com

Abstract Background: Dengue is the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world. As per the WHO guidelines for dengue fever, a list of atypical or unusual manifestations also termed ‘Expanded Dengue Syndrome’ are mentioned. Objectives: Our objective was to identify and compare the distribution of Expanded Dengue Syndrome in pregnant and non-pregnant women. Materials and Methods: In this prospective observational study 370 non-pregnant female patientswith NS1 antigen and/or IgM dengue antibody positive status were included. Along with this to increase our understanding of the consequences of dengue virus infection during pregnancy, a prospective analysis was performed among 22 pregnant females who developed dengue fever during pregnancy. The study was conducted at Kamineni Hospitals, L B Nagar, Hyderabad from September 2017 to September 2019. The distribution of expanded dengue syndrome was studied and compared with the help of chi-square test. Results: Expanded Dengue Syndrome was seen in 4.59 % (17 out of 370) of non-pregnant women and 27.19% ( 6 out of 22 ) pregnant women with dengue fever and it was found to be statistically significant. Among the 370 non pregnant women, Hepatitis was found in 3 patients (0.81%), CNS involvement was present in 2 patients (0.54%), Myocarditis in one patient (0.27%), Acalculouscholecystitis in one patient (0.27%) and Pneumonia was found in 10 patients(2.7%).Among the 22 pregnant women with dengue fever Expanded Dengue Syndrome was found in 6 patients, which were Hepatitis in one patient (4.55%), Encephalitis in one patient (4.55%) and Pneumonia in 4 patients (18.18%). Conclusion: In the study population, there was a statistically significant increase in the percentage of Expanded dengue syndrome in pregnant women than in non-pregnant women. So a high index of clinical suspicion is essential in any pregnant woman with fever during epidemic. Key Words: Acalculouscholecystitis, Dengue fever, Expanded dengue syndrome, Hepatitis, Myocarditis, Pneumonia

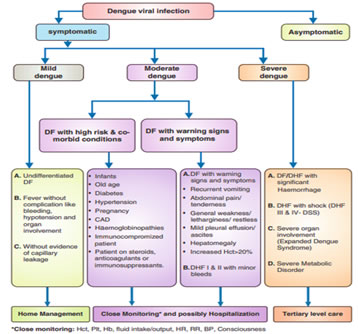

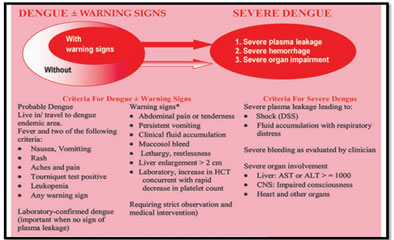

INTRODUCTION Dengue is the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world. In the last 50 years, incidence has increased 30-fold 1.Almost half of the world’s population live in countries where dengue is epidemic. WHO estimates that 50-100 million dengue infections occur every year with 22000 deaths. Dengue is endemic in more than 100 countries of which most cases are reported from Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific regions 2. In India, an increase in dengue incidence has been observed in past few decades and its outbreaks have been frequently reported from different parts of the country in both urban and rural populations 3-8. Thus, dengue has become a major global public health concern. Dengue virus is a small single-stranded RNA virus comprising four distinct serotypes namely, DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3 and DEN-4. These closely related serotypes of the dengue virus belong to the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae. Various serotypes of the dengue virus are transmitted to humans through the bites of infected Aedes mosquitoes, principally Aedesaegypti.9 In the recent decade more cases of dengue in pregnancy are being reported. The clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of dengue in pregnant women are similar to those of non-pregnant women but with some important differences.10,11 In order to recognize and diagnose dengue disease early in pregnancy, clinicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion when dealing with pregnant women who present with febrile illness after travelling to, or living in dengue-endemic areas. The Expanded Dengue Syndrome was studied among the study population with the help of WHO classification of Dengue (described in Figure no: 1 and 2). According to this classification, dengue is classified into the following grades.

Figure 1: Dengue Case classification19,20

Figure 2: Dengue case classification by severity21 As per the WHO guidelines for dengue fever, a list of atypical or unusual manifestations also termed ‘Expanded Dengue Syndrome’ are mentioned which are described below.

These could be explained as complications of severe profound shock or associated with underlying host conditions/diseases or co-infections. Table 1: Clinical manifestations observed in Expanded Dengue Syndrome20

MATERIALS AND METHODS It is a prospective observational study done in Kamineni academy of medical sciences and research centre. Data was collected from pregnant and non-pregnant women admitted in Department of General Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology with probable dengue fever. CBP, Haematocrit, Dengue NS1, Ig M andIg G for Dengue were sent in all patients who presented with probable Dengue fever. All female patients more than or equal to 18 years with NS1 antigen and/or IgM dengue antibody positive status were studied. A detailed history taking and examination was performed in all patients. Pregnant females diagnosed with Dengue fever were included irrespective of their gestational age. Other investigations like LFT,RFT,PT,APTT,INR,USG Abdomen,(Shielded) Chest X ray, ABG etc. were done depending on the clinical scenario. Sample size was calculated using the formula : Z2 x p x q / n2, where Z=Standard normal deviate =1.96[correspond to confidence level of 95 %], p = Prevalence of laboratory confirmed dengue infection among clinically suspected patients = 38.3 % [according to Study on Dengue Infection in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis in 2017 by Ganeshkumar p, Murhekar MV, Poornima V, Saravankumar V, Sukumaran K, Andaselvankar et al..], q = 1 – p =1 – 0.38 = 0.62, Degree of accuracy=0.05.So sample size was found to be :1.96² X 0.38 X 0.62 / 0.05² ≈ 362, rounded to 370 .Along with 370 non –pregnant women 22 pregnant women were also included in the study. Inclusion criteria All females with age ≥ 18 years with Dengue NS1 positive status or Dengue Ig M positive status or both Dengue NS1 , Ig M positive status or both Dengue NS1 and/or Ig M positive status with Ig G positive status were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria Females with age < 18 years and females showing positive status only for DengueIg G were excluded. Statistical analysis: Data was entered into Microsoft excel data sheet and was analysed using SPSS Trial version 2018 software. MS Excel, SPSS Trial version 2018 was used to analyse data. Categorical data was represented in the form of Frequencies and proportions. Chi-square test was used as test of significance for qualitative data. MS Excel and MS word was used to obtain graphs. p value(probability that the result is true) of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant after assuming all the rules of statistical tests. OBJECTIVE Our objective was to identify and compare the distribution of Expanded Dengue Syndrome in pregnant and non-pregnant females.

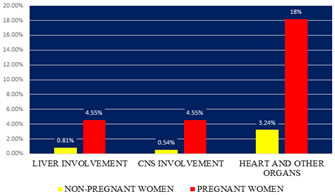

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS Expanded Dengue Syndrome was seen in 4.59 % (17 out of 370) of non-pregnant women and 27.19%( 6 out of 22 ) pregnant women with dengue fever and it was found to be statistically significant. Among the 370 non pregnant women, Hepatitis was found in 3 patients (0.81%), CNS involvement was present in 2 patients (0.54%), Myocarditis in one patient (0.27%), Acalculouscholecystitis in one patient (0.27%) and Pneumonia was found in 10 patients(2.7%). The two patients with CNS involvement had generalised tonic clonic seizure due to encephalitis. Among the 22 pregnant women with dengue fever Expanded Dengue Syndrome was found as Hepatitis in one patient (4.55%), Encephalitis in one patient (4.55%) and Pneumonia in 4 patients (18.18%). In the study population, there was a statistically significant increase in the percentage of Expanded dengue syndrome in pregnant women than in non-pregnant women.

Table 2: Distribution of Expanded dengue syndrome among non pregnant women

Table 3: Distribution of Expanded dengue syndrome

Chi square statistic is 7.07.The p-value is 0.029. The result is significant at p < 0.05

Figure 3: Distribution of Expanded dengue syndrome in the study population

DISCUSSION “Dengue is one disease entity with different clinical presentations and often with unpredictable clinical evolution and outcome”. Expanded dengue syndrome was coined by WHO in the year 2012 to describe cases which do not fall into either dengue shock syndrome or dengue hemorrhagic fever. The atypical manifestations noted in expanded dengue are multisystemic and multifaceted with organ involvement, such as liver, brain, heart, kidney, and CNS14. The clinical profile of 370 non-pregnant women and 22 pregnant women were collected and data was analyzed. The age of patients with dengue fever among the non-pregnant women ranged from 18 to 81 years and in the pregnant women ranged from 18 to 34 years. The mean age was 38.9 and 24.6 years in non-pregnant and pregnant women respectively. Clinical features suggestive of Expanded Dengue Syndrome were identified and analysed statistically. Expanded Dengue Syndrome was seen in 4.59 % (17 out of 370) of non pregnant women and 27.19%( 6 out of 22 ) pregnant women with dengue fever and it was found to be statistically significant. Lee et al... observed transaminitis in 30% of patients15.Acalculouscholecystitis has been documented in many case reports. A study by Bhatty et al... in 2009 reported 27.5% of cases as acalculous cholecystitis16. In a study series by Mohanty et al.. 21.3% cases of cholecystitis were identified. These patients had an increased levels of alkaline phosphatase, thickened gallbladder wall, and pericholecystic fluid collection17. The pathogenesis of acute acalculouscholecystitis is still unclear. Many factors are thought to contribute to liver dysfunction. They are hypoxic injury due to decreased perfusion, direct damage by the virus, and immune‑mediated injury. Shaprio et al.. in his studies showed that cholestasis, increased bile viscosity, and infection are the probable causes18.

CONCLUSION Dengue is a challenging disease with multi-systemic, varied, atypical and sometimes life-threatening presentations. Awareness of these rare manifestations goes a long way in early recognition, correct diagnosis, prompt intervention, and appropriate treatment. Every aspect of dengue viral infection remains a clinical challenge. Dengue in pregnancy requires early diagnosis and treatment. Health-care providers should consider dengue as the differential diagnosis in pregnant women with fever during epidemics in endemic areas and be aware that clinical presentation may be atypical . Early diagnosis is made difficult by the ambiguity of clinical findings and physiological changes of pregnancy that may confuse the clinician. In the absence of associated feto-maternal complications, infection by itself does not appear to be an indication for obstetric interference. Further studies and systematic reviews are mandatory as evidence-based data in the management specific for pregnant patients are inadequate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We must acknowledge the Department of General Medicine and Obstetrics and Gynaecology, at Kamineni Hospital, where we have acquired most of our experience. We should also thank our colleagues and staff of Departments of General medicine and Obstetrics and Gynaecology who provided an atmosphere suitable for carrying out this work. Above all we thank all the patients and attendants who have co-operated with us in this study by giving their valuable consent.

REFERENCES

Policy for Articles with Open Access: Authors who publish with MedPulse International Journal of Pediatrics (Print ISSN: 2579-0897) (Online ISSN: 2636-4662) agree to the following terms: Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post links to their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home

Home