|

Table of Content - Volume 16 Issue 3 - December 2020

Risk factor for hearing loss from acute bacterial meningitis in infant

Swati Jain1*, Ashwini Kundalwal1, Girish Shakuntal1, Snehal Patil1, Leena Jain2

1Department of Pediatrics, 2Department of ENT, SMBT Medical College and Research Centre, Dhamangaon, Igatpuri, INDIA. Email: drswatijain85@gmail.com

Abstract Background: To identify the risk factor significantly associated with higher incidence of hearing loss in infants with acute bacterial meningitis (ABM). Methods: It was an ambispective observational study carried out in paediatric department of medical college and tertiary care centre in Northern Maharashtra. Total of 50 infant who had done hearing assessment after acute bacterial meningitis were included. After history and physical examination, CSF cytology, biochemistry and culture sensitivity were sent. Imaging of brain was done if required. Ear examination was done to rule out any cause for conductive hearing loss. An audiological assessment of the patient was done at the time of discharge using BERA. Results: Of the 50 children, 13(26%) developed sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) following ABM. SNHL was bilateral in 7(14%) and unilateral in 6(12%) cases. 3(6%) had mild SNHL, 5(10%) had moderate SNHL, 4(8%) had severe and 1(2%) had profound hearing loss. Of the various variables correlated with hearing loss, CSF pleocytosis, raised protein content and low sugar level in the CSF, Modified GCS < or = 8 and altered sensorium were significantly associated with increased risk of developing hearing loss. Conclusions: 26% infants developed sensorineural hearing loss after ABM which emphasizes the need for audiological evaluation of a child after meningitis. BERA is a helpful tool for assessment of hearing loss especially in the young children. There is limited facility for BERA testing in our country especially in rural area. Early identification is essential for successful rehabilitation, including cochlear implantation and speech therapy. So, if we know the significant risk factor for hearing loss in infant with ABM, timely referral can detect hearing loss early and rehabilitation can be done. Keywords: SNHL (sensorineural hearing loss), ABM (acute bacterial meningitis), BERA- (Brainstem Evoked Response Audiometry), CSF- (cerebrospinal fluid)

INTRODUCTION Deafness is one of the most common serious complication of acute bacterial meningitis (ABM) in children.1 Complete or partial Deafness occurs in 5% to 35% of survivors of meningitis. Profound bilateral hearing loss will occur in up to 4% of patients.2 It is one of the leading cause for acquired deafness in infancy and childhood and accounts for 90% of all causes of acquired hearing impairment by the age of 3 years.3,4 It is the result of cochlear or auditory nerve inflammation.5 Most meningitis-associated SNHL emerge in the acute stage of meningitis and remain stable after recovery, but there can be spontaneous regressions, fluctuations, or progressions in hearing after recovery from meningitis.6 Early identification is essential for successful rehabilitation, including cochlear implantation.7 School-aged survivors of meningitis have functionally important disabilities, including neurologic or central auditory perceptual dysfunction, that adversely affect learning ability, academic performance, and behavior.8 Hearing loss in very early life can affect the development of speech and language, social and emotional development and communication skills, social adjustment and academic achievement of the young child. Hearing assessment is difficult in infants. Auditory brain stem evoked response (ABER) is used to assess hearing in this population.9 Early intervention could be done if SNHL detected early, which if left untreated may lead to serious handicap affecting the overall development of child. Assessment of hearing in children after meningitis is recommended.5 since there are very few Indian studies in above context, we decided to conduct this study to identify the risk factor significantly associated with higher incidence of hearing loss in infants with acute bacterial meningitis.

METHODS It was an ambispective observational study conducted in pediatric department of tertiary care hospital in northern Maharashtra after obtaining the requisite permission of Ethical Committee of the hospital. Fifty infants with positive CSF for ABM were enrolled in the study with written informed consent from parents. Children with age more than 1 year, history of neurodevelopmental delay, tubercular meningitis, head injury, associated comorbid condition like HIV infection, heart disease, neural tube defects or Pathological hyperbilirubinemia in newborn period were excluded from study. Details were recorded in a pre-decided proforma including age, gender, history for high grade fever, hypothermia, vomiting, irritability, excessive or inconsolable cry, refusal to feed, altered sensorium/lethargy, convulsion, followed by complete physical examination. ABM was treated as per standard guidelines. Some patients were also given dexamethasone. Radio imaging of brain was done if required. Ear examination was done by otorhinolaryngologist in all cases to rule out causes for conductive hearing loss. An audiological assessment of the patient was done at the time of discharge using Brainstem Evoked Response Audiometry (BERA). The data was presented in an excel sheet and analyzed statistically using SPSS 17 software. Results were tabulated based on cases with SNHL and without SNHL against various parameters like age, sex, presenting symptoms, clinical signs and investigation like WBC count, CSF total cell count, protein and sugar and its statistical significance is calculated using Pearson’s chi- square test and Fisher’s exact test and unpaired t test. P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ethical approval: taken

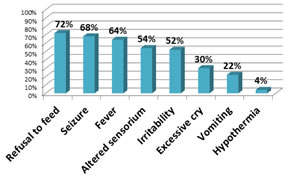

RESULTS Cases were categorized into two groups as those with SNHL present (group I) and SNHL absent (group II). Of the 50 children with ABM, 25(50%) were less than one month old, 19(38%) were 1-6 month, 6(12%) were 6-12 month of age. majority of the children with ABM were below 1 month of age. 28(56%) were females and 22(44%) were males. Female to male ratio was 1.27:1. Refusal to feed, seizure and fever were the most common presenting symptoms in our study. (figure 1). figure 1: proportion of various clinical features in children with ABM

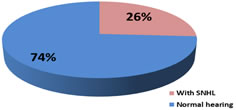

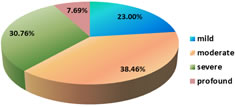

22(44%) had abnormal imaging (USG/CT/MRI) of Brain. Among abnormal findings; 9(18%) had only Hydrocephalous, 4(8%) had Acute infarcts, 3(6%) had Subdural effusion and Cerebral oedema, 2(4%) had Ventriculitis with hydrocephalous and 1(2%) had Subdural hemorrhage. Hydrocephalus being the most common abnormal finding was seen in 11 cases. 13(26%) out of 50 children developed SNHL following acute bacterial meningitis. (Figure 2) SNHL was bilateral in 7(14%) and unilateral in 6(12%) cases. Most of cases have moderate hearing loss. (Figure 3) Figure 2: Distribution of SNHL in infant with acute bacterial meningitis

Figure 3: severity of SNHL in infant with acute bacterial meningitis Various clinical variables like age, sex, fever, seizure, altered sensorium, GCS, serum WBC count, CSF total cell count and protein and glucose levels were selected and individually analyzed to evaluate its marginal association with hearing loss. In our study, 8 children below 1 month of age, 4 children between 1-6 month of age and 1 child between 6-12 month of age developed SNHL. Incidence of SHNL was more in infants below one month. (Table 1) It was observed that incidence of SHNL was decreased as age increases but this trend is not statistically significant (p value=0.3). Table 1: Association among the cases between – Age and SNHL

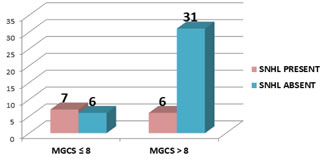

25% of females and 27.27% of males developed SNHL, but no correlation was found between gender and occurrence of SHNL. (p value =1). Mean days of illness before admission was 3.44 days. There was no relationship found between no. of days of illness before treatment and development of SNHL. Amongst 27 cases with altered sensorium, 9 developed SNHL, which suggests that there is increased risk of development of SNHL in patient with altered sensorium in ABM which was statistically found to be significant (P- value 0.04). Amongst 13 cases with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) less ≤ 8, 7 developed SNHL. Risk of developing SNHL was found to be higher in patient who had GCS less than 8. (Figure 4) This correlation was found statistically significant (P value 0.02).

Figure 4: Comparison of Modified Glasgow coma scale and development of SNHL Seizures and fever were more common in children who developed SNHL compared to those without SNHL but there was no significant correlation between fever, seizure and development of hearing loss in patient with ABM. Out of the 13 cases of SNHL, etiology could be identified in 5(38.4%) cases. S. Pneumoniae, E. coli, Klebsiella, Gram positive cocci, Gram negative bacilli were responsible for 1 case each. In this study Administration of Dexamethasone and Amikacin had no bearing in the development of hearing loss. (Table 2)

Table 2: potential risk factor for hearing loss in acute bacterial meningitis*

*Data are given as no. of patient (percentage)with the variable in the category Mean ± SD for WBC count for group I was 14691.5±7225.2 while for group II it was 15915.1±9834.2. There was no significant difference in WBC count between 2 groups. Mean ± SD for CSF Total nucleated cells and CSF protein was more for group I in comparison with group II. Patient with higher value for CSF Total Neutrophil count and protein had more incidence of SNHL. (Table 3) Mean ± SD for CSF glucose (mg/dl) was less for group I than group II. Patient with low value for CSF glucose have more SNHL. Among 9 cases with CSF sugar less than 20, 5 developed SNHL, which was statistically significant (P value 0.03). Risk of developing SNHL is higher in patient who have CSF glucose less than 20. Among 23 cases who had abnormal imaging of brain, 10 developed SNHL. Though patients with abnormal imaging of brain had more SNHL but this observation was not statistically significant in our study. Table 3: CSF Correlates in acute bacterial meningitis

DISCUSSION Of the 50 children enrolled in the study, 13(26%) developed SNHL following acute bacterial meningitis which was found comparable to other studies.9,10,11 Widely variable incidence of SNHL in ABM has been reported in studies done in India. Variations of incidence ranged from 36.6% to 64% on higher end while in some studies reported much lower incidence of 6%- 7%. 12,13,14 15,16 In our study, 6% had mild SNHL, 10% had moderate, 8% had severe and 2% had profound SNHL. In study done by Cherian et al... 3.14% had mild SNHL, 12.47% had moderate, and 12.47% had severe profound SNHL.10 In a study by Singh et al.., 6.6% had severe and 30% had moderate SNHL.13 These variations in the incidence and type of SNHL can be due to various other factor affecting development of SNHL in patient with ABM Such as nutritional status, susceptible age as younger the child greater the risk of SNHL, immunization status, temporal delay in management. In our study no correlation could have been established between etiologic agent of meningitis and hearing loss as definite etiology for ABM could not be identified in most of cases. Higher incidence of hearing loss is seen in pneumococcal meningitis.5,17,18 In our study infant less than 1 month old and male gender had more hearing loss but no significant association was found between age, gender and hearing loss. Age and gender of the patient were not significant risk factor for hearing impairment in other study also.11 In present study, patients with fever and seizure have higher incidence of hearing loss but this tendency does not reach statistical significance. Seizures are common complication of meningitis. In our study, 68% of patients had seizure. Out of 13 patients with hearing loss, 84.6% had Seizures compared with 62.1% of those with normal hearing. The cause of seizure in the ABM may be different than that of hearing loss. In a study by Charuvanij et al., no significant correlation was observed between hearing loss and various clinical and demographic factor.19 Cherian et al. observed that the total duration of fever was significantly different in those with and without SNHL (P < 0.05) but presence of seizure was not significantly associated with SNHL.10 Seizure was found to be a strong predictor for hearing loss in ABM in various other studies.12,13,18,20 In our study, altered sensorium and GCS <8 were significantly associated with increased risk of SNHL in patient with ABM (P value = 0.04 and 0.02). Depressed level of consciousness bears significant correlation to the development of SNHL as suggested by most studies except the study done by Cherian et al...10,12,21. In our study CBC parameter were not significantly associated with hearing impairment. CSF pleocytosis was significantly associated with development of SNHL in the present study with p value of 0.003 and was consistent with other studies where CSF pleocytosis was strongly correlated with hearing loss.22,23 (Table 4) In study by Bhatt SM, onset of hearing loss was proceeded by a CSF leukocytosis of > 2000 cells/ mm3.22 Increased CSF protein levels were significantly associated with SNHL in the present study with p value of 0.036 which was found to be consistent with other studies where high protein in CSF was associated with a significantly higher risk of hearing loss.10,11 Association of low CSF sugar with SNHL was statistically significant in the present study (P value = 0.006) which was found to be similar with the other study.11,23In study by Kapoor et al.. , CSF sugar (<20mg%) was significantly associated with abnormal BAER (P value< 0.05).12Among 18 cases who received dexamethasone, 6 developed SNHL. Dexamethasone therapy was not associated with decreases incidence of hearing loss in present study which was comparable with other studies.17,24 Contrary to above observation, significant reduction in incidence of hearing loss was observed after dexamethasone therapy by Girgis NM et al... .25.10Among 45 cases who received Amikacin (aminoglycoside), 12 developed SNHL. In present study, amikacin was not associated with increased risk of SNHL, which was similar to another study, where aminoglycoside usage were not significantly different in those with and without SNHL. Thus ototoxic drugs do not seem to have any effect in the development of SNHL. Patients with abnormal imaging of brain had more SNHL, but there was no correlation found between abnormal imaging of brain and increased incidence of SNHL in present study, this is similar to study by Singh K et al.., where no relation was observed with hydrocephalous, subdural effusion and higher incidence of SNHL.13

Table 4: Association of hearing loss with various CSF parameters in ABM in different studies

CONCLUSION There is high incidence of sensorineural hearing loss following acute bacterial meningitis in infant. Altered sensorium, MGCS <8, CSF pleocytosis, raised CSF protein, decrease CSF glucose <20 are significant risk factor for development of hearing loss in infant with acute bacterial meningitis. Our study emphasizes the need for complete audiological evaluation of a child recovered from meningitis. BERA is a helpful tool for screening the sensorineural hearing loss especially in the young children and infants in whom other conventional methods may not be of much use. Hearing impairment may lead to serious handicap affecting the linguistic performance and overall development of the child. There is limited facility for BERA testing in our country especially in rural area. Early identification is essential for successful rehabilitation, including cochlear implantation and speech therapy. So, if we know the significant risk factor for hearing loss in infant with ABM, timely referral can detect hearing loss early and early intervention can be done.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to thank the consultant paediatricians, audiologists, microbiologists, and the resident doctor and nursing staff of paediatric department of SMBT medical college and research centre, Dhamangaon, Igatpuri.

REFERENCES Richardson MP, Reid A, Tarlow MJ, Rudd PT. Hearing loss during bacterial meningitis. Arch Dis Child. 1997; 76 134- 138.

Jama and Archives Journals. Risk Factors Identified For Hearing Loss In Children With Bacterial Meningitis. Science Daily. [Internet]. 2006, September 25. .Available from: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/09/060918192239.htm

Vernon M. Meningitis and deafness: the problem, its physical, audiological, Psychological, and educational manifestations in deaf children. Laryngoscope. 1967 Oct; 77(10):1856-1874.

Fortnum HM. Hearing impairment after bacterial meningitis: a review. Arch Dis Child. 1992 Sep; 67(9):1128-1133.

Janowski AB, Hunstad DA. Acute Bacterial Meningitis beyond the neonatal period. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 21th ed. Philadelphia: ELSEVIER; 2020: 3223-3232.

Brookhouser PE, Auslander MC, Meskan ME. The pattern and stability of Postmeningitic hearing loss in children. Laryngoscope. 1988 Sep; 98(9):940-948.

Grimwood K, Anderson VA, Bond L, Catroppa C, Hore RL, Keir EH et al... Adverse outcomes of bacterial meningitis in school-age survivors. Pediatrics. 1995 May; 95(5):646-656.

Roine, I. Peltola, H. Fernández et al..., Influence of admission findings on death and neurological outcome from childhood bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46(8):1248-1252.

Girgis NI, Farid Z, Mikhail IA et al... Dexamethasone treatment for bacterial meningitis in children and adults. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989 Dec;8(12):848-851.

Policy for Articles with Open Access: Authors who publish with MedPulse International Journal of Pediatrics (Print ISSN: 2579-0897) (Online ISSN: 2636-4662) agree to the following terms: Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post links to their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home

Home