|

Table of Content - Volume 3 Issue 3- September 2016

Atypical presentation of acute myocardial infarction

Rajshekhar I Koujalgi

Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Bidar Institute of Medical Sciences, Bidar-585401, Karnataka, INDIA. Email: rajshekharik@gmail.com

Abstract Objectives: To study atypical presentation of Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) and time delay from symptom onset to hospital presentation in local population. Subjects and Methods: Acute Myocardial infarction (AMI) patients (316) admitted to Government Bidar Institute of Medical Sciences (BRIMS) Hospital., Bidar, situated in a semi-urban backward district of north Karnataka, studied over a period of 1 years with atypical(without chest pain) and typical(with chest pain) presentation along with site of infarct, risk factors, time delay from symptom onset to hospital presentation thrombolysis and mortality were studied. Observations: Out of 316 AMI studied, 273(86.39%) presented with chest pain and 43(13.60%) with atypical symptoms and mean age being 51.3 and 56.3 years respectively. Dyspnoea(39.53%) being most common atypical symptom followed by vomiting(32.55%) and syncope(25.58%), noted frequently in inferior wall Myocardial infarction (IWMI 23/43patients-53.48%). When considered atypical Vs typical, atypical presentation was associated with increased percentage in females (32.55% vs 21.97%) and hypertensives, equal incidence in patients with angina and diabetes. More atypical Myocardial Infarction (MI) delayed (>6 hours) presenting to hospital (44.19% vs. 30.04%), underwent lesser (41.86% vs. 61.53% ) thrombolysis(statistically significant) and more mortality(30.23% vs. 19.41%). Conclusion: A higher index of suspicion is needed for early recognition of Atypical MI associated with older age group, females, hypertensives and presenting with dyspnoea, vomiting, syncope, to avoid time-delay in reperfusion therapy and subsequent mortality. Key Words: Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), Atypical AMI, Typical AMI.

Cardiovascular diseases are major causes of mortality and morbidity in the Indian subcontinent, causing more than 25% of deaths. It has been predicted that these diseases will increase rapidly in India and this country will be host to more than half the cases of heart disease in the world within the next 15 years1. The World Health Organization requires the presence of chest pain as one of the cornerstone features in the diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction(MI).2 The absence of chest pain at initial presentation was among the most significant factors predicting lower use of thrombolytic therapy among a subset of MI patients eligible for such treatments in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 (NRMI-2)3. Understanding the factors associated with atypical presentation (ie, no chest pain) may help in the earlier identification and treatment of these patients with MI.

MATERIAL AND METHODS 316 patients of AMI admitted to Government BRIMS Hospital, Bidar, over one year from July 2016 to July 2017 were studied from admission to discharge. AMI was diagnosed by clinical features, ECG changes and or enzyme abnormalities. The criteria of ECG changes are-

Patient’s age, gender, presenting symptom of typical chest pain or atypical symptoms at onset of AMI such as dyspnoea, syncope, vomiting, sweating, backache, jaw pain etc., the time-delay from symptom onset to hospital presentation, history of Ischemic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and thrombolytic therapy, with in-hospital mortality were noted. The findings were recorded and tabulated. Statistical analysis was performed on the results applying chi square goodness of fit test. P value <0.05 were considered significant.

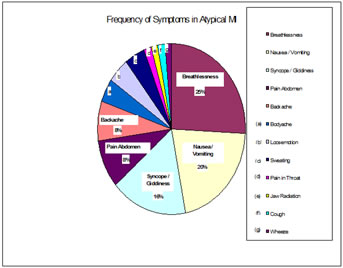

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS Out of 316 AMI patients studied, 273 (86.39%) presented with chest pain (Typical ‘A’ group) and 43 (13.60%) presented with atypical symptoms (‘B’ Group). Atypical symptoms included acute dyspnoea (39.53%) being most common followed by vomiting (32.55%), syncope (25.58%), backache, sweating and others (Table-IIa). Out of total 316 AMI, AWMI (anterior wall MI) was the commonest (63.60 %) followed by IWMI (35.44 %).In Group ‘A’ patients, AWMI was more frequent(66.66%) while in Group ‘B’ patients IWMI (53.48%) was more common than AWMI (25.58%). (TABLE-I) Atypical MI (group B) incidence was maximum (27.90%) between age 65 to 74 yrs. Group ‘B’ was associated with more percent of elderly (> 60 years-48.83%), Females (32.55%), Hypertensives (23.25%),who underwent less thrombolysis (41.86%) and showed increased mortality (30.23%) in comparison to group ‘A’ patients (Table 2) More percentage of group ‘B’ patients (44.19%) delayed presenting to the hospital(> 6 hours) in comparison to group ‘A’(30.04%).Though more percentage of patients in both age group (< 60 years 27.91%,>60 years 16.28%), both genders(male 32.56%, female 11.63%),diabetes (4.63%), IHD (4.65%), hypertension (11.63%) were associated with delayed presentation (>6 hours) to the hospital when compared to group ‘A’ (Table 1) but were found statistically not significant. Less percentage of patients in group ‘B’(25.58%) underwent thrombolysis on initial presentation(<6 hours) when compared to group ‘A’ (50.92%) which was found statistically significant(p= 0.0000001).More percentage of mortality was observed in group ‘B’ with IWMI(37.50% -Table 2 b) and especially in patients presenting later than 6 hours (16.28%) in comparison to group ‘A’(Table-1)

Table 1: Characteristics of Time delay from symptom onset to hospital presentation

Table 2: Characteristics of Time delay from symptom onset to hospital presentation

Figure 1

DISCUSSION The presentation of acute MI with atypical symptoms, such as syncope, vomiting, sweating, dyspnoea with wheezing, acute backache etc., has always been very misleading to the healing physician and the patient. This is likely to delay the diagnosis and institution of appropriate treatment for the patient. In our study of 316 patients with acute MI as many as 43 patients (13.60%), presented with symptoms other than chestpain (Group ‘B’). Many studies also have made similar observations. For instance, in Reykjavik study4 30% of patient with acute MI had no chest pain but only atypical symptoms on presentation to hospital. Study by Canto et al5 showed patients with atypical MI when compared to typical MI were older( 74.2 yrs vs. 66.9 yrs). William B. kannel et al6 in Framingham update study showed there was a linear increase in the incidence of acute MI with atypical symptoms according to the age groups 55 to 64 years and 65 to 74 years as 27% and 31% respectively. Our study shows similar incidence of 26% and 28% in the same age group respectively. In study by canto et al5 females dominate the patients who present with atypical symptoms 49% vs typical MI 38% and similar observations in a study by Muller RT et al 7, (more percentage of females (32.55%) were noted in atypical MI group) but again no such finding was noted in our study. In our study atypical MI showed a lower prevalence(3 patients) of angina (statistically not significant). This is comparable with Framingham study8 and Honolulu heart program study9. The lower frequency of prior history of angina in the atypical MI group suggested a reduced sensitivity to ischemic pain. In Framingham study8 as well as in Honolulu Hawai Heart program study9 the patients with atypical symptoms were more likely to be hypertensive, to have diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance is comparable to our study only in hypertensive group and not significantly in diabetic group. Study by Canto et al5 showed MI patients without chest pain showed a longer delay before hospital presentation(mean 7.9 vs 5.3 hours),whereas our study showed both atypical and typical presentation had longer delay ( mean 13.31 vs 13.19 hours) compared to above study. Canto et al5 showed MI patients without chest pain were less likely to receive thrombolysis or primary angioplasty (25.3% vs 74.0%), which is comparable to our study where atypical MI received less thrombolysis than the typical MI (41.86% vs 61.53%) which was found statistically significant P 0.014. Henry et al study, for patients presenting ≤1 hour,>1 to 2 hours, and >2 to 3 hours, >9 to 10 hours, >10 to 11 hours, and >11 to 12 hours after symptom onset, the use of any reperfusion therapy were 77%, 77%, 73%, 53%, 50%, and 46% respectively11; which is comparable to the present study where 69.77% patients presenting <6 hrs after onset of AMI symptoms were thrombolysed compared to 35.64% who presented >6 hrs, was found statistically significant P<0.001. Possible explanations for the relationship between delay in hospital presentation and use of any reperfusion and timeliness of reperfusion therapy include: (a) patients who present early after onset of symptoms may elicit more urgency from providers to initiate reperfusion therapy; and (b) patients who present late may exhibit more atypical or no symptoms which subsequently lead to missed or late diagnosis as well as confusion or reluctance to administer reperfusion therapy10 The frequency of inferior wall MI compared to AWMI among the patients presenting with painless infarction was observed in few studies5,9 but not in Framingham studies8,10. That is, higher proportion of inferior wall MI tends to cause atypical symptoms, such as epigastric pain or abdominal distress which would fail to be recognized as MI. In our study there is a dominance of IWMI in the group B(with atypical symptoms 23 out of 43 patients) (Statistically significant), and surprisingly the mortality in their group was also higher(9 out of 43) than with AWMI(4 out of 43). However the mortality in group A patients (N 273) in our study was higher among AWMI group compared to IWMI group. Patients with atypical MI group showed a higher mortality than did the typical MI group (30.23% vs. 19.41%) though statistically not significant. In the Framingham study8also, age adjusted long term mortality for all cases were slightly worse among unrecognized MI cases than among recognized MI. But this is in contrast to Reykjavik study2, where the prognosis for patients with atypical MI is no better than that for patients with recognized MI. The Worchester heart attack study12 findings showed Case fatality did not differ significantly with delay of arrival at the hospital. In contrast, according to United Kingdom Heart attack study13, case fatality did not differ significantly for delays up to 12 hours, but it was higher for patients who delayed for more than 12 hours. In our study in- hospital mortality for early arrivers (<6hrs) was 19.06% and that for late arrivers (>6hrs) 24.75% is comparable though statistically not significant. CONCLUSION In this study of 316 AMI, 273 had typical and 43(13.60%) had atypical presentation with dyspnoea as the commonest symptom followed by vomiting, syncope and others, were associated more often with elderly, females, IWMI, hypertensives, less in angina patients, similar percent of diabetics, had higher mortality. Although statistically insignificant, probably because of the limited sample population. Increase in the delay of arrival after onset of MI symptom was associated with 1. Increase in age. 2. Female sex. 3. Atypical symptoms. 4. Increase in the mortality rate were however found statistically not significant, but 5. Decreased thrombolysis was found statistically significant. Atypical MI is not less severe than typical. This emphasizes the need for a high suspicion index in many different clinical settings, but particularly although not exclusively in elderly, females, in the presence of unexplained paroxysmal dyspnoea, or otherwise vomiting, syncope, abdominal pain. With the knowledge that delay in hospital presentation negatively impacts use of any and timeliness in administering reperfusion therapy, attention should be focused on logistical and system issues for providers and patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I acknowledge my thanks to the cooperation of patients, The Director BRIMS Bidar for extending clinical and laboratory facilities at BRIMS hospital for this study, Late Prof. Dr. M.S. Rao Former National President API. for his blessings, without which the research manuscript would have been incomplete, Prof. Dr V.V. Hara Gopal. Department of Statistics, Osmania University Hyderabad for statistical analysis and Mr. Anand Patil for preparation of manuscript.

REFERENCE

Policy for Articles with Open Access

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Home

Home